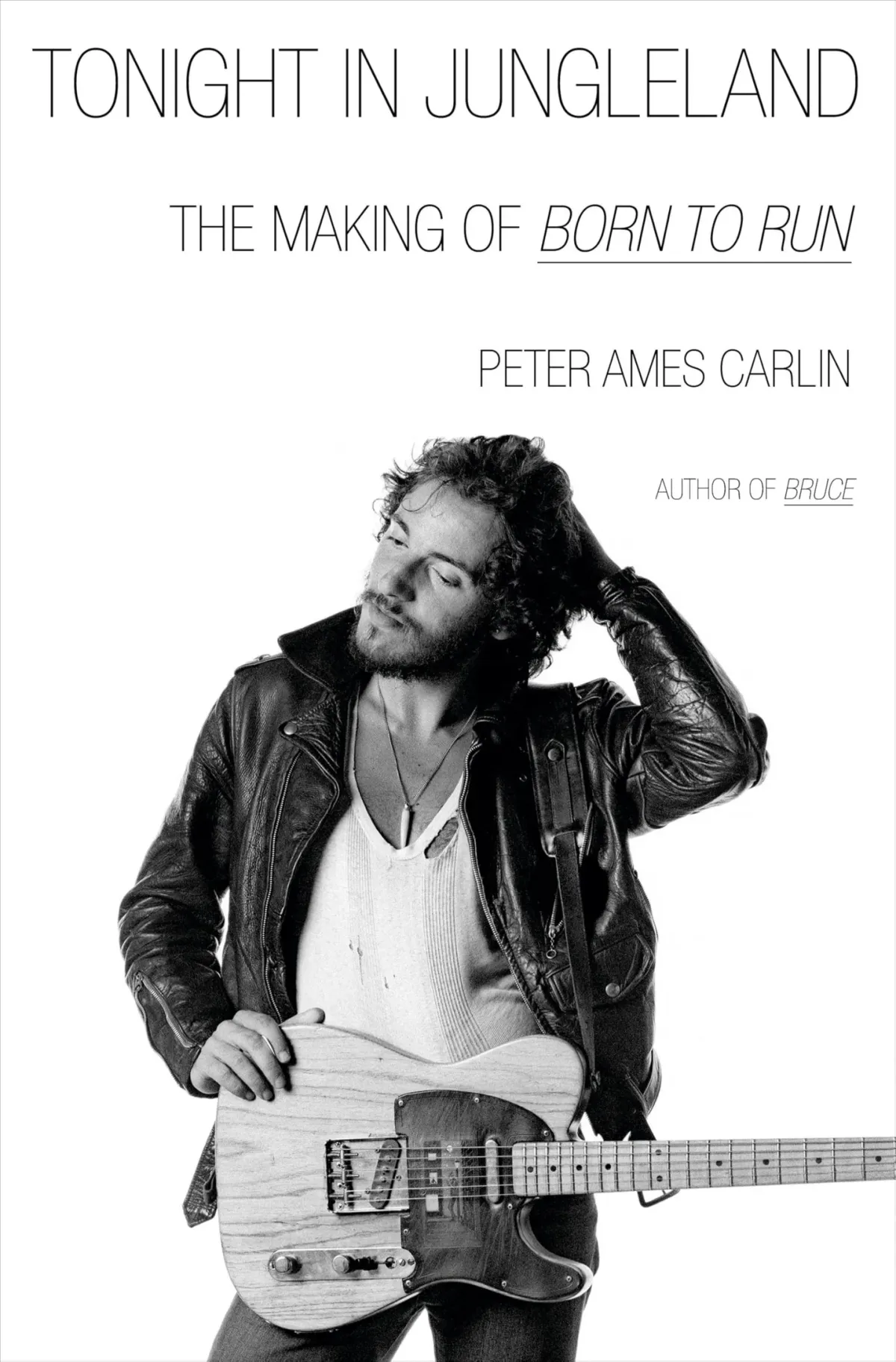

When Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run hit the streets 50 years ago, Lester Bangs wrote in Creem that the album “reminds us what it’s like to love rock ‘n’ roll like you just discovered it, and then seize it and make it your own with certainty and precision.” Other accolades poured in. Greil Marcus, writing in Rolling Stone, called it “a magnificent album that pays off on every bet ever placed on him—a ’57 Chevy running on melted down Crytsals records that shuts down every claim [for him] that has ever been made.” Billboard declared that the album’s title track was a “monster song with a piledriver arrangement . . . simply one of the best rock anthems to individual freedom ever created.” The making of that pivotal moment is the subject of a new book, Tonight in Jungleland: The Making of Born to Run (Doubleday, August 5), by Peter Ames Carlin.

The praise for Born to Run was quite heady for an artist whose first two albums had not lived up to their promise, at least in the eyes of his record label. Sales from Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. and The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle were disappointing, even though critics hailed the arrival of this young singer and songwriter as the next Dylan. In Newsday, Robert Christgau reflected on Springsteen’s first album, 1973’s Greetings from Asbury Park: “His songs are filled with absurdist energy and bleeding-heart pretension that made Dylan a genius instead of a talent . . . Springsteen has potential, and I’ll play his next album the day I get it.”

Despite the critical support for his first two albums, and Jon Landau’s now-famous announcement that he “saw the rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen,” by 1975 his future didn’t look as rosy as it had two years earlier. He still rocked the joint when he hit the stages of any venue—and he prided himself on his ability to get the audiences up and dancing their cares away—but the young rocker needed a hit record, and his confidence in himself as a writer was waning. As Carlin writes, “What had been a land of dreams had awakened in the withering light of an unforgiving dawn. Bruce’s own sense of possibility, at least when it came to his life as a recording artist, had begun to fracture.”