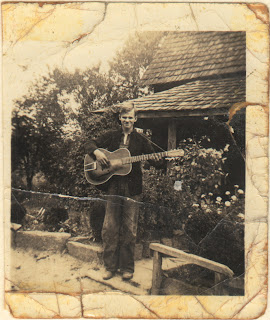

Blind But Now I See provides a chronological history of Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson’s life and career beginning with Doc’s childhood in Deep Gap, North Carolina. Despite his disability (Watson was blind from just after birth), Doc Watson enjoyed a childhood of relative freedom and independence. As one of nine children, Watson came from a large family that did their best not to coddle him or treat him any more differently than necessary. As the book recounts, Watson often claims that his father putting him to work on one end of a crosscut saw cutting timber at the age of fourteen was the best gift he could receive. Not only did it teach him the value of hard work (a trait very present in his musical training), but it also instilled in him a sense of worth and purpose. A gift his father gave him at an earlier age was equally important: a fretless, homemade banjo whose head was made from the hide of his grandmother’s recently deceased cat. This was Doc’s first stringed instrument, and after a few quick lessons from his father, he began to learn and experiment on his own. Eventually, of course, Doc found his way to the guitar where he would become one of the most renowned players in the world. As Gustavson recounts, however, his “discovery” in the hills of North Carolina was more a product of luck than grand design.

Folklorist and musician Ralph Rinzler traveled to the Appalachia's in 1960 hoping to track down old-time musician Clarence Ashley. Rinzler had heard Ashley’s haunting mountain songs on the venerable Smithsonian Anthology of American Folk Music albums, sounding to him as if they had come from another century. The young New Yorker managed to track down Ashley in Tennessee and had arranged a recording session with the fiddle and banjo player. Ashley, in turn, gathered a group of musicians to back him at the recording, one of which was Doc Watson who arrived for the session with his electric Fender Telecaster. Doc had been making his living playing honky-tonk, rockabilly, and western swing at parties in the hills of North Carolina, expanding his repertoire well beyond the traditional mountain songs he learned as a child. Of course, Rinzler was looking precisely for that old-time mountain music, and Doc’s Telecaster didn’t fit into this vision. Guitar players the world over should be glad Doc grudgingly borrowed an acoustic guitar for the sessions, otherwise he would likely be the greatest electric guitarist in the hills of rural North Carolina that no one ever hear of.

Fortunately, though, Doc’s incredible playing was given an audience as Rinzler organized concerts for the Clarence Ashley group in urban cities across the country. Eventually, Watson’s stunning virtuosity, natural charisma, and plain-spoken intelligence began to outshine his fellow musicians to the point that Rinzler worked to establish Watson as a solo folk act in his own right. At this point, Doc Watson was almost forty years old, with a wife and two children living quite humbly in North Carolina. Blind But Now I See goes to great pains to illustrate Rinzler’s role in developing Doc’s career (at the sacrifice of Rinzler's own career as a musician), including his presentation of Doc as an “authentic” Appalachian folk musician, a classification that would come to feel a little too constraining for someone with a varied musical appetite like Watson. Eventually, the flat picking genius would incorporate his many influences into his playing and song choices, but early on Rinzler strongly urged that he stick to a very traditional play list as he orchestrated Doc’s tours though the folkie coffee-house circuit of the 1960’s.

Watson’s first years traveling on the road by himself are described as troubled times for the middle-aged blind musician who had rarely traveled outside his native region. It is not until his son, Merle, learns to play guitar at age fifteen and joins him on the road that Doc can more easily withstand the rigors of travel. Merle played a hugely important role in his father’s career, acting as his road manager, driver, and gifted accompanist. From the book’s description, it seems unlikely that Doc could have sustained a regular touring regime were it not for his son. Merle also played an important role in Doc’s musical development. The son’s distinctive finger-picking and slide playing offered a perfect counterbalance to Doc’s flatpicking virtuosity. As Merle grew to become a wildly talented musician in his own right, he also began to act as a liaison of sorts between his father and younger musicians of the newgrass era. While Merle was a great source of joy and success for Doc’s musical life, Gustavson’s text also relates how the son became the greatest source of grief for Doc’s personal life.

Merle died at a tragically young age due to a tractor accident in his mid-30’s. However, Merle’s personal demons had been a source of heartache for the family even before his death. The young guitar player had long struggled with drug and alcohol abuse, including multiple stints in rehab. Gustavson indicates that Merle had a notorious history of being unreliable over the years, sometimes leaving his father in compromised situations. The author also describes a good deal of ambiguity surrounding the role that substance abuse could have played the night of Merle’s death. Not a mystery, however, is the devastating toll Merle’s death placed on Doc and his wife, Rosa Lee. Blind But Now I See describes Doc as a changed man after Merle’s death. While he was able to continue forward with his career, Doc became much more closed off and deeply protective of his privacy after Merle’s death. While Doc’s music, even since the death of Merle, offers such rich and profound expressions of joy, the book describes a continuing emotional life darkly shadowed by grief and loss.

Though deeply tragic, it seems almost perversely fitting that Watson’s life should be framed by such desolate grief. This only reinforces the perception of Watson as something almost mythical in the folk history of American music. A quote in Blind But Now I See from fiddler Darol Anger describes Doc’s legendary status like this:

“There was a feeling… that Doc was sort of like a spectacular natural feature of the landscape; inevitable, fully formed, iconic. He seemed ageless, and his so-called disability and spectacular transcendence of that along with his folksy manner made him a kind of mythic character, sort of a household god.”

If I had to offer any faults for the book, it would be a slight tendency towards this hero worship by the author himself, especially in the earliest chapters of the book. I find it hard to hold this against Gustavson, however, given Doc’s extraordinary legacy in American music. There are few mortals who deserve to be put on a pedestal, but it’s hard to argue about a man who so embodies American ideals of hard work, humility, personal integrity, triumph over adversity, and, of course, supernatural talent. Given his strong religious faith and genuine spiritual yearning (a trait explored in depth in the text), Doc would undoubtedly recoil at any hint towards making him a Deity. I don’t care what he says, though; if there is a God, I’m sure even He can’t play guitar like Doc Watson.

__________________________

Dustin Ogdin is a freelance writer and journalist based in Nashville, TN. His work has been featured by MTV News, the Associated Press, and various other stops in the vast environs of the world wide web. His personal blog and home base is Ear•Tyme Music. Click below to read more and network with Dustin.

Ear•Tyme blog...

Facebook...

Tweets...

Comments ()