Sometimes the circle really is unbroken. Consider that the seeds of Levon Helm's new album Dirt Farmer and the intimate "Midnight Ramble" concerts he performs in his home studio were planted on a cotton farm in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas. Helm's dad, Jason Diamond Helm, met his future wife Nell when he was playing guitar at a house party that charged two bits a head and served white lightning in fruit jars. The couple had four children; Levon was the second, born in 1940. J.D. taught Levon "Sitting On Top Of The World" when Levon was 4 years old, and the parents taught their children songs such as "Little Birds" and "The Girl I Left Behind", both of which are on Dirt Farmer.

Levon's first concert memory is of Bill Monroe & His Blue Grass Boys in 1946, when Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs were still in the band. One of the shows he recalls from nearby Helena, Arkansas, was the F.S. Walcott Rabbits Foot Minstrels; years later, Robbie Robertson would mine those memories (and slightly change the name) to write "The W.S. Walcott Medicine Show". Young Levon looked forward to when he would be old enough to attend the more risque revue known as the Midnight Ramble.

Amy Helm was born in 1970 in Woodstock, New York. Her drummer dad Levon had joined rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins in the late 1950s; together, Helm and Hawkins went to Canada and found four other guys to fill out the band, making it Ronnie Hawkins & the Hawks. The Hawks would later be hired by Bob Dylan to back him on his first mid-'60s electric tour. Then the Hawks became The Band and released two remarkable records of almost incomparable influence, 1968's Music From Big Pink and 1969's self-titled album. Amy's mom, Libby Titus, put out an LP in 1977 that included her enduring co-write with Eric Kaz, "Love Has No Pride". After breaking up with Helm in the mid-'70s, Titus was seriously linked with Dr. John; in 1993, she married Donald Fagen of Steely Dan. Levon has been married to Sandra Dodd since 1981.

On Thanksgiving Day in 1976, The Band essentially ended with The Last Waltz, a concert at San Francisco's Winterland that was filmed by Martin Scorsese and featured The Band playing with such musical influences and peers as Muddy Waters, Van Morrison and Bob Dylan. Excepting essential studio footage shot with Emmylou Harris and the Staple Singers, principal songwriter and guitarist Robbie Robertson would never again perform with the group, which reunited without him in 1983 but never came close to regaining the glory of its past. Robertson would also never again make such fine music.

The 1990s were tough on Helm. In 1991, his Woodstock home and adjoining recording studio burned to the ground. Helm rebuilt -- now there are no nails in the vaulted ceiling of the recording room -- but the wolf was at the door, and he declared bankruptcy three times to protect his property. Then the singer who inhabited songs such as "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" and "Rag Mama Rag" was diagnosed with throat cancer. After 28 radiation treatments, Helm beat the cancer, but his voice was reduced to a whispery rasp.

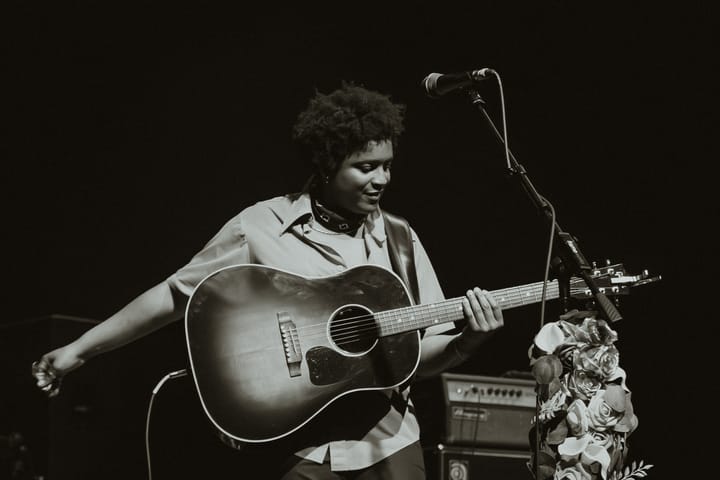

By then, Amy Helm had graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a degree in psychology and was singing in a variety of bands around New York City. She joined her father in the Barn Burners, a blues band he formed while in recovery. "There was no grieving about losing his voice," says Amy, "because we were so grateful that he'd survived the cancer. For the Barn Burners, he put all his efforts into drumming. He changed the way he set up his kit, and really attacked the drums."

Slowly, Levon's voice returned, scratchier than before but still very soulful. "He and I started to sing a little bit with each other," Amy says. "I remember one day he taught me the words to a few of the old hymns, and I recorded him with a little hand-held tape recorder so I could learn the tunes. I was excited when I listened to it back, because his voice was getting stronger."

As the Barn Burners became the Levon Helm Band, Amy was finding her own niche as a member of Ollabelle. Levon reportedly had health insurance, but the bout with cancer had driven him deeper into debt. His Midnight Ramble house-concerts conjure a communal affair, but they're really old-fashioned rent parties, though instead of costing two bits, the "contribution" for the early, occasional Ramble was $100. These days there's about two a month, and the price is $150.

Larry Campbell, a multi-instrumentalist who spent seven years on the road with Bob Dylan, loves playing the Ramble. "For those two hours, you're doing exactly what you'd hoped you'd be doing with your life," he says. "I remember early on when I was playing with Bob, and there was something like 50,000 people out there, and we're doing 'Forever Young' at the end of the show and I thought, 'Man, this is pretty cool.' And that's one of how many songs? But this Ramble is something else, like the audience are friends or family. That's what it feels like, so there's no anxiety."

And from intimate, small-town concerts, a fine record has emerged. "I had wanted for years for my dad to record an album of songs that he had taught to me," says Amy, "some of which he had learned from his parents. We started recording songs just to document them without a real vision of where it might lead, and it just sort of took shape as we went."

Campbell, who'd already produced Ollabelle's second outing, quickly agreed to play and help with the sessions. "All the music that means anything to me, the genuine American music -- blues, rock 'n' roll, country, bluegrass, gospel -- Levon can perform and sing with complete authority," Campbell says. "That's what The Band did back in the day -- they took all these relatively disparate genres and blended them into one unique thing. Levon's my favorite singer in the world. And it's not that he learned how to do this; he just is it."

Campbell says he wanted to make "an acoustic album with some sass to it," and tunes such as Paul Kennerley's "Got Me A Woman" and J.B. Lenoir's "Feelin' Good" more than meet that criterion. Steve Earle's "The Mountain" was recorded the very day Helm first heard the song on Amy Goodman's "Democracy Now" program; Levon set it to a 4/4 rhythm at his daughter's suggestion. The result is a song that boasts not just background vocals by Buddy & Julie Miller, but the wooden thump of a song by The Band.

The music of Dirt Farmer reflects the casual nature in which it was made; the singing and playing is accomplished, but also favors feel over virtuosity. That's often the preference for a natural musician, and few are as nonchalantly gifted as Helm. He hits the snare drum like a natural rock 'n' roller, and he's a born singer; can you hear anybody else when you read the words, "Catch a cannonball now, t'take me down the line?" There's also something terribly moving about having a familiar voice brought back from silence, damaged yet distinct, and as comfy as a good warm coat.

Woodstock, New York, has been known as a rural artist destination since the early 1900s, with painters, writers and musicians drawn to Byrdcliffe, Maverick, and other art colonies, scenes, and schools. The music world followed Albert Grossman in the early 1960s, especially when the influential folk and rock manager's most famous client, Bob Dylan, moved to town. Dylan put Woodstock on the rock 'n' roll map, but not long after the 1969 festival in Bethel that bore the town's name, Dylan and his family fled to Greenwich Village. Dylan is ancient history in Woodstock, but the story of The Band, who came to town and made music in a house known as Big Pink, continues to haunt these hills.

The chamber-group like alchemy of The Band is what made them special. I first saw them live at their Fillmore East debut in 1969, and it remains one of my richest concert memories. It's hard to name a group whose vocal and instrumental interplay was as soulfully textured as that of The Band, which besides Helm consisted of Robertson on guitar, Rick Danko on bass, Richard Manuel on keyboards and drums, and Garth Hudson on a variety of keyboards and horns. Having three distinctive lead singers in Manuel, Helm, and Danko proved the ultimate ace in the hole.

The story of The Band, however, is also enough to make you cry. Helm chose not to talk to No Depression for this story, but after his 1993 autobiography, This Wheel's On Fire, everybody knows his venomous regard for Robertson (an arguably more balanced telling of The Band's story can be found in Barney Hoskyns' Across The Great Divide). Helm's main beef is that Robertson took sole credit for songs that Helm says were honed by the group during rehearsals and recording sessions.

Disputes over publishing rights are a familiar story, and can kill a band (U2, for one, chooses to share credit equally). Some believe that if a group member contributes significantly to a song's arrangement, that member deserves part of the writing royalty, and indeed, songwriters sometimes give a share of the publishing to uncredited colleagues. In this case, one could also argue that Robertson's lyrics borrowed from Helm's stories of the south.

It's useful, in any event, to examine the songwriting credits on Music From Big Pink and The Band. The former includes four songs by Robertson, three by Manuel, one Bob Dylan song, and two Dylan co-writes, one with Danko and another with Manuel. On The Band, Robertson has eight solo songs, three collaborations with Manuel, and one with Helm. The extraordinary ensemble work that characterizes these records might rightfully suggest all members deserved a piece of the publishing, but at the same time, Robertson was clearly doing the heavy lifting in terms of songwriting.

Two wrinkles in the story suggest why Robertson became the public and songwriting face of the group that, following its departure from Ronnie Hawkins, was known as Levon & the Hawks. The first was Helm's decision to leave the Dylan tour toward the end of 1965 because he hated the booing with which folk fans greeted the singer's more aggressive rock sound. The others soldiered on with a different drummer, and can be heard on Volume 4 of Dylan's Bootleg series, Live 1966.

Robertson likely studied not just Dylan, a singer-songwriter at the peak of his powers, but also his manager. After Dylan's motorcycle accident in July 1966, the former Hawks, who were on retainer to Dylan, moved to Woodstock. Robertson rented a house with his girlfriend, and Danko, Manuel, and Hudson moved into a house in nearby West Saugerties that would become known as Big Pink. Helm rejoined his mates in late 1967, after Grossman got the group a deal with Capitol Records.

Meanwhile, Dylan and Robertson would come by Big Pink daily to write and record all manner of covers and originals in a basement Hudson had wired up for recording. (Selections from the much-bootlegged sessions were eventually released as The Basement Tapes.) Part of the plan was for the prolific Dylan to write new tunes that could be covered by other artists. Grossman created a publishing firm for these songs called Dwarf Music; when Dylan later discovered that he'd also helped himself to half the proceeds, it precipitated nearly two decades of litigation between Dylan and his soon to be ex-manager. What does this have to do with The Band? All of the songs on Music From Big Pink, including "The Weight", are published by Dwarf Music.

Musicians ignore business at their own peril, and from the evidence of Helm's own book, he and the others were too busy with music, sex, drugs and booze to pay much attention. "The first royalty checks we got almost killed some of us," said Danko, as quoted in Helm's book. "'This Wheel's On Fire' was never really a hit, but it had been recorded by a few people, and all of a sudden I got a couple hundred thousand dollars out of left field....Dealing with this wasn't in the fuckin' manual, man!"

Life became even more of a carnival when the group began to tour after their self-titled album was released in 1969. The Band was always a great live act -- Rock Of Ages, recorded in 1971 with horn arrangements by Allen Toussaint, remains an in-concert classic -- but compare the performance clips from 1970's Festival Express and 1976's The Last Waltz, and it's easy to see they were living fast and hard.

Artistically, The Band was never better than on its first two albums, though 1970's Stage Fright had its moments, and 1975's Northern LightsSouthern Cross was regarded as a return to form. Robertson was certainly no choirboy, but between strained communication, drunken car accidents, and the sad fact that alcoholism had reduced Manuel to a shadow of his gifted past, it's little wonder he wanted to call it quits after The Last Waltz.

Helm grumbled that Scorsese's film was shot as if it were Robertson's Hollywood screen test, and though Robertson did star in 1980's Carny, it was Helm who found a second career as a fine character actor in such movies as Coal Miner's Daughter, The Right Stuff, and the recent Shooter. For Robertson, though, Scorsese was like the new Dylan, a great artist from whom he could learn. The players in The Band got loaded and drove their cars fast. Robertson and Scorsese snorted coke and screened Kurosawa movies. That's why The Last Waltz really was the last dance.

Woodstock is a small town, and if you listen to the wind in the pines, you can almost hear The Band. I moved here in 1992 and live in a house a couple hundred yards from where Amy Helm was possibly conceived. I dutifully found Big Pink (not easy), and am blessed to play with musicians whose connections to The Band go as far back as 1969. Hell, my cleaning lady used to work for Albert Grossman, who died on a trans-Atlantic flight in 1986, and who was buried behind his Woodstock restaurant, the Bear. Incidentally, there's a Snickers bar in the casket.

Richard Manuel sang "I Shall Be Released" at Grossman's funeral, grateful, perhaps, for how he'd looked after the troubled singer. A little over a month later, The Band played a show at the Cheek To Cheek Lounge in Winter Park, Florida. Late that night, Manuel used a leather belt to hang himself to death from the shower rod in his room at the Quality Inn. He was buried in Canada, and "I Shall Be Released" was played on the organ by Garth Hudson.

Helm had talked to Manuel just hours before his suicide, and part of the conversation was about the bummer of playing clubs after you've jetted around the country on a big-time 1974 tour with Bob Dylan (documented on the double-album Before The Flood). "We're just musicians," Helm told Manuel. "We're just working for the crowd. It's the best we can do."

The Band went on with new players, and pursued other options. Helm and Danko signed on with Ringo Starr's All-Starr Band, and Danko worked with Eric Andersen and Jonas Fjeld. Hudson did studio sessions and toured with Marianne Faithfull. But the years caught up with Danko, who was busted in Japan in 1996 for receiving a packet of heroin in the mail, and his weight ballooned. Danko could still charm a club, and darn near anybody in Woodstock, but on December 10, 1999, his body cried uncle, and he died in his sleep.

Helm skipped the public memorial at the Bearsville Theater because Robertson gave the eulogy. He'd also declined to attend The Band's 1994 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Helm is both bitter and full of pride, but in any event, his plate was already full. He had survived throat cancer to sing again.

"He's the last voice standing," says Jimmy Vivino, who plays guitar with the Max Weinberg 7 on "Late Night With Conan O'Brien", played with Helm in the Barn Burners and does so now at the Rambles. Vivino is a rock scholar -- he's also part of a top-tier Beatles band, the Fab Faux -- and relishes the chance to play with Helm. "You lock into that snare drum," he says, "and it's like riding in a classic car."

Helm loves, and maybe even lives, to play. Not long ago, Amy was booked for a gig in Woodstock with Larry Campbell and Campbell's wife Teresa Williams (who also sings on Dirt Farmer). Dad slipped into the club unannounced and settled behind a drum kit. But Helm can also play the big towns: He and the Ramble crew have lately played sold-out shows in New York City, traveled to Nashville to play the Ryman Auditorium, and have booked an appearance at Merlefest in North Carolina for the spring of 2008.

"Playing the Ryman with Levon was almost like a Nashville Last Waltz," says Campbell of a show that included appearances by Emmylou Harris, John Hiatt and Ricky Skaggs. "For musicians on the singer-songwriter side of Nashville, the people who are there because they're artists, Levon holds a high level of respect."

That's because everybody loves a natural. "Whenever I'm onstage with Levon, I feel like I'm sitting in a comfortable chair somewhere, like on a porch, playing," says Campbell, relaxing at a picnic table outside Helm's studio. It's Saturday night, and Campbell had spent the week doing television appearances in Patti Scialfa's band and preparing for two months on the road with Phil Lesh & Friends. "That's what it feels like. There's no cranial thing involved. You're just reacting to him and he's reacting to you."

Levon's Midnight Ramble starts at 8 p.m. and is a discreet mile or two from the middle of town. Volunteers help get the cars parked on a grassy field, and others wear "Helmland Security" T-shirts. In a town that takes its zoning seriously, Levon has found a way to do his thing (so did Albert). A couple of years ago, his people successfully petitioned the town board to declare "Levon Helm Day." There's merchandise for sale in the basement space and a table for guests to share potluck snacks. On Helm's website, you can "Sponsor a Square" by donating $500 to help get him out of debt.

The action is upstairs in a majestic studio defined by blue stone walls and a massive cathedral ceiling. The sound at the Ramble is studio sharp; the crowd sits and stands around a central area covered with oriental rugs and filled with amplifiers, microphones, a grand piano, and a drum kit. Elvis Costello and Gillian Welch are among a long list of famous musicians who have dropped in to play; other times the opening acts include a regional blues band and whomever is recording at the studio.

Helm enters to great cheers about two hours into the show. His smile is wide, and not surprisingly, he seems right at home. Over two Saturday nights, highlights included a rollicking "Rag Mama Rag" with Helm on mandolin, a stark reading of Bruce Springsteen's "Atlantic City", a version of "Ophelia" featuring a New Orleans-style horn section, and a jumpy take on the new "Got Me A Woman". Campbell and Vivino tangled on guitars and sang songs by The Band, while Little Sammy Davis blew some great blues harp. Helm ended each night with "The Weight", which was interesting given that he'd recently filed a lawsuit claiming he was not adequately compensated for the use of the song in a cell phone commercial. Helm is unlikely to win the case, but at the Ramble, the song makes the crowd feel as if they'd been lucky enough to sneak into the basement of Big Pink.

Dirt Farmer closes with Buddy & Julie Miller's "Wide River To Cross" (Campbell was in the Buddy Miller Band almost 30 years ago). "There's a sorrow in the wind, blowing down the road I've been," goes a verse that concludes, "I've come a long, long road, but still I've got some miles to go/I've got a wide, wide river to cross."

Levon Helm always said that his stool behind the drum kit is the best seat in the house, but at the Ramble, standing mere feet from his snare drum comes in a close second. Helm has said that "the snare is where the backbeat lives," and when he smacks the rim, you feel it in your bones. Helm is now 67, and he's still singing "(I Don't Want To) Hang Up My Rock And Roll Shoes". If this isn't exactly the life he'd planned, it's also the culmination of all he has known. The boy who couldn't wait to go to the Midnight Ramble has created one of his own.

John Milward is a writer and musician. His band the Comfy Chair once shared a stage with Levon Helm at the Volunteer's Day picnic in Woodstock.

Comments ()