"...I take direction, I don't take dictation. And it's not for any reason other than that I just feel like I know what I'm doing better than anybody else knows what I'm doing."

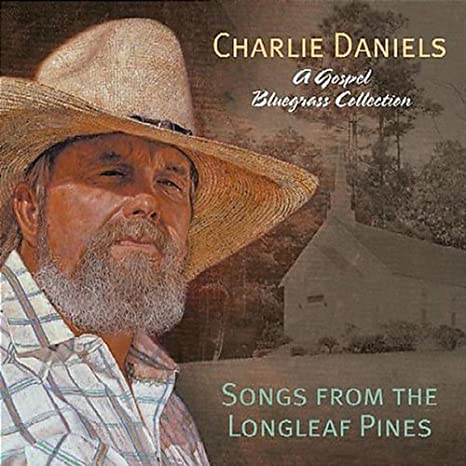

On the back of the Charlie Daniels Band's Essential Super Hits, there's a picture of the Charlie known to almost everyone -- burly, wearing a hat that threatens to rival Hoss Cartwright's in the size of its crown, and shredding the horsehair off his fiddle bow. The cover of his new album, Songs From The Longleaf Pines (Koch/Blue Hat), tells another side of the story. An illustration rather than a photograph, Daniels looks subdued, almost contemplative, in a more modest straw western hat and a plain checked shirt. And if the music isn't quite as restrained as the portrait might suggest, it's still bluegrass, it's still all gospel, and it reflects a side of Daniels that's even older than the aggressively-patriotic and country-rockin' ones which have been his stock in trade for years.

"The first real band I was ever in was a bluegrass band," says Daniels, who was born in Wilmington on the North Carolina coast in 1936. He was 15 and living in the central part of the state when a friend -- Russell Palmer, the man to whom Longleaf Pines is dedicated -- showed him his first chord on the guitar.

"I went to his house one day, and he had an old Stella guitar -- it had a neck half the size of a fencepost, old strings, all that stuff," Daniels recalls with a laugh. "And he knew a couple of chords on it. I said, 'Man, you gotta teach me that.' You know, there are a lot of people these days who play music, guitars and stuff, but hardly anyone did back then. Just a very few people.

"So he showed me a D chord, and we started playing together. Then somebody showed up with a mandolin one day, so I had to get into that, and then I switched over and started playing fiddle. Bluegrass was pretty big down there, because Flatt & Scruggs spent a time on the radio at Raleigh, and they were very well thought of. And of course we used to listen to Bill Monroe, anybody like that. So Russell started playing five-string banjo, and eventually -- probably around 1953 or 1954 -- we put together a bluegrass band, and played any place they'd let us play."

Still, even in North Carolina the possibility of making a living playing bluegrass was impossibly remote in those days, and when Daniels did make the leap to a full-time gig a few years later, it was as a club musician in the beer joints of Jacksonville. He brushed up against bluegrass again for a while in the late 1960s and early 1970s -- by then he'd moved to Nashville to work as a studio musician -- when he was tapped to play twelve-string guitar on some of Flatt & Scruggs' last recording sessions, and then to back Scruggs and his sons in what would become the Earl Scruggs Revue.

After that, though, he turned to original music, creating the Charlie Daniels Band. Walking a line between country and southern rock that found occasional radio success ("The Devil Went Down To Georgia" was #1 country and #3 pop in 1979, earning a CMA award for Single of the Year), Daniels built and maintained a sizable and devoted audience. But though he was known for an energetic, good-time style with a healthy streak of good ol' country-boy orneriness, he had other things on his mind, too.

"Christian music -- gospel music -- has been a strong part of my heritage," he notes. "I come from a Christian family -- I am a Christian -- and I love the music. I wanted to do a gospel album for many years, but we were always on major labels. Major labels don't do that much anymore; they leave it to smaller companies like Sparrow, who have the expertise and the placement capabilities to promote gospel music.

"Well, Sparrow and Capitol are both owned by EMI, and when we were on Capitol, Sparrow got to looking over the roster to see if there was anybody that they wanted to do a gospel album, and they picked us. So I said, 'Yeah, I've been waiting.' And I immediately set about writing the songs for it."

Daniels' first gospel album, The Door, won the Gospel Music Association's Dove award for Country Album of the Year in 1995. A cut from its follow-up, Steel Witness, earned another Dove two years later. In 2001, Daniels released a collection of old favorites -- "'Amazing Grace', and 'Life's Railway To Heaven', all the old songs we used to sing in church," he recounts. So when he was approached with the idea of making a bluegrass gospel album, the combination of his earliest and most recent experiences and predilections made his assent not only inevitable but enthusiastic.

"It's just kind of early life revisited," he says. "I felt very much at home when we did this thing."

Even the title, though it wasn't Daniels' idea, contributed to the backward look. "The state tree of North Carolina is the longleaf pine, and back when I was a kid, there were pristine growths of longleaf pine trees, which is just a much prettier tree than a shortleaf pine," he explains. "They don't plant them anymore because they grow so slow, so they're kind of a disappearing tree. But my dad was in the timber business, and so when I think about North Carolina, when I think about my youth -- the early times, the formative years of my life -- I think of the longleaf pines, and it just seemed liked a natural title."

The songs, too, are largely drawn from Daniels' formative years. "As far as I'm concerned," he says, "they are the cream, the royalty of bluegrass gospel music." Many are associated indelibly with Bill Monroe, from his own "The Old Crossroads", to "What Would You Give (In Exchange For Your Soul)", the first record by the Monroe Brothers, to "Walking In Jerusalem (Just Like John)", which opens the album.

Earl Scruggs is on board for a reprise of Flatt & Scruggs' "Preachin', Prayin', Singin'", originally recorded around the time Daniels learned that D chord. Mac Wiseman, the Whites and the GrooveGrass Boyz -- basically the Del McCoury Band minus Del -- play prominent roles throughout the album.

Among the songs featuring Wiseman is "The Old Account" -- the second time within a decade Wiseman has cut the song, and not by coincidence. He suggested it to Daniels; an earlier version that features Wiseman's warm lead vocals appeared as a hidden track on a 1997 GrooveGrass Boyz album (and again as the second cut on 1998's Mac, Doc & Del). Both albums were produced, as was Longleaf Pines, by Scott Rouse, a North Carolinian who detoured into pop and comedy production with the likes of New Kids On The Block and Jeff Foxworthy before connecting with hardcore bluegrassers such as McCoury and Blue Highway.

Rouse brought an innovative slant on sound and arrangement to the project, one that fit well with Daniels' approach. "I'd go in the studio with the guys and say, 'Hey, let's try this, let's try that.' And it just worked out," Daniels says. "Of course, we put a little 'CD' [Charlie Daniels] on it, you know. I can't do something without doing that, it's just natural for me to do it. It's just the way I hear things -- I hear them in certain arrangements and in certain ways, and I like trying new things."

The result is that while the album rests on bluegrass bedrock, it's rife with touches that distinguish it from the mainstream. There's Daniels' voice, of course -- craggy and declamatory, it's hardly compatible with traditional bluegrass vocalizing and tight harmonies. But beyond that, Rouse isn't afraid to liven up the production with what, for bluegrass at least, are cutting-edge innovations: the sound is hot, dry and in your face, and when the instruments stop in the middle of a song, it sounds more like a digital snip than hands damping strings.

Yet though Rouse contributed significantly to the project, it's very much a Charlie Daniels record. "It's a little different, and that's intentional," he allows. "I did a cut a while ago for a compilation that one of the big companies did, and their A&R man called back and wanted to remix my song. I asked him why, and he said that it didn't sound like everything else on the album. I said, 'Do you know how hard I strive to keep from sounding like everybody else? You're paying me a compliment. I don't want to sound like everybody else.'

"That's the way I like to operate. I work well with producers. If we're doing a project and I get a guy to work with me producing, I work well, and I take his advice well, but I take direction, I don't take dictation. And it's not for any reason other than that I just feel like I know what I'm doing better than anybody else knows what I'm doing."

Still, Daniels says, he appreciates the values of traditional bluegrass, and he's not surprised that it has enjoyed a resurgence of popularity. "You know," he notes, "there's a whole new generation now that didn't even know what bluegrass music was until that O Brother movie came out. It got to the point where radio stations were literally forced into playing 'I'm A Man Of Constant Sorrow'. And people started hearing it and couldn't get enough of it -- it was something new, it was something fresh, it was something different. This bluegrass music is simple. It's easy on the ears. It makes you want to snap your fingers. And there's an honesty to it that very few other kinds of music have. There's no pretension.

"It's just straight-ahead -- five or six guys wailing away. What is happening is what they're creating right there at that moment. They're not going to play it the same way next time. They're not going to play it exactly like they did the last time they played it. There's a simplicity and an honesty, a transparency that you don't find in a lot of kinds of music. And I think people respond to that."

At the same time, Daniels is hardly committing himself to staying in that vein, though he's not averse to the idea of doing more bluegrass in the future. "It's another facet of me," he explains. "The next album that I'm planning on doing will be totally different from this -- or from anything else we've done.

"I intend to spend the rest of my career doing what I want to do, simply because I've got a lot of different kinds of music in me that the world has never heard. It's the time in my career that I just feel that, if I'm ever going to explore these other facets that I feel within myself, I've got to do it now. I may go back and do another bluegrass album one of these days. I may just do a straight bluegrass album -- I don't know. Whatever feels good is what I want to do. I don't have another thirty years to think about it, so it's time to get it on now."

ND contributing editor Jon Weisberger is a bass player, songwriter and journalist who recently relocated to Madison, Tennessee, where he lives just up the street from John Hartford's old house.

Comments ()